As the camera shutter clicks, Jesi Taylor Cruz, lips slightly parted, pink nails gently pressed against blushed cheekbones, tries to channel one of the contestants from America’s Next Top Model, their favorite show growing up. The nails are important. This shoot, part of a project called Prim-n-Poppin, is inspired by sixties- and seventies-era cosmetics advertisements, and Cruz’s job is to sell that polish. Well, sort of.

It’s September 2019 and the Williamsburg, Brooklyn studio of beauty photographer Julia Comita is a flurry of activity. Hairstylist Raina D. Leon coifs one model to retro perfection while makeup artist Brenna Drury puts the finishing touches on another’s pastel eyeshadow. Still, Cruz remains focused, thinking, What would Tyra say to me right now?

After all, this moment is one Cruz had set sights on since moving to Brooklyn from Florida at age 19: “At some point when I came to New York, I don’t remember exactly what sparked it, but I thought, ‘One day, I’m going to be in an ad for something.’”

Those words entering Cruz’s mind, even a few years prior, would have seemed almost unimaginable. When the vitiligo that now affects large portions of Cruz’s face and body first appeared at age 15, the model and graduate student, who is pansexual and non-binary, tried everything to hide the condition, which is marked by the loss of skin color in patches. Acutely aware of the stares of teenage peers—weird, strange, deformed, they must have been thinking—Cruz’s first true experience with makeup was mired in shame. “I was so self-conscious, I wouldn’t leave my bedroom until I had a full face of foundation on,” Cruz shares with OprahMag.com.

Thinking back on it now, at 30, Cruz is confident that if positive images of other faces with vitiligo had appeared in magazine editorials or advertisements at that time, things might have been different. Maybe classmates, better accustomed to seeing models proudly flaunting a unique patchwork of skin tones, would have been kinder. Maybe the bulimia that continues to affect Cruz to this day, even years into recovery, would have loosened its insidious grip sooner.

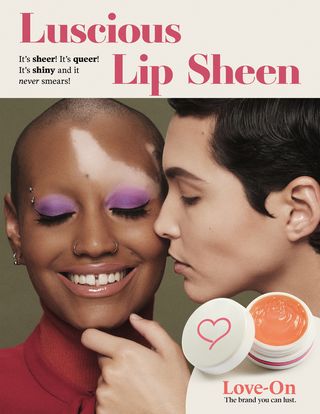

And that’s the larger mission of Prim-n-Poppin, a reimagined collection of vintage-style cosmetic ads featuring a diverse mix of queer and gender non-conforming models: to present an alternative idea to the mostly white, mostly thin, mostly cisgender notion of beauty perpetuated by advertising imagery for decades.

The brainchild of Comita and Drury, Prim-n-Poppin (prim, a reference to days of yore; poppin, a nod to modern slang), was initially conceived as a meaningful way for the two creatives to collaborate. But as they scanned the mood board Drury had created for their first meeting, a greater purpose began to materialize. “We started saying, ‘Ok, what do we see when we look at these old ads?’” Comita explains. “They’re funny. They’re really cheesy. Oh, and by the way, it’s all young white women. They were obviously missing a diverse group of people, and that’s who we wanted to see.”

One lipstick ad, in particular, struck a dissonant chord with Drury. In it, a woman wistfully stares into the camera as a man, unnervingly close, caresses her face. Beneath the image, a line of text reads, “Your lips look luscious, babe.” To Drury, who identifies as queer and has a girlfriend, everything about it was just wrong. “The woman doesn’t look happy and the copy basically says to make your lips look sexy for a man,” she recalls. “It made me very uncomfortable.”

The very idea of feeling comfortable—in one’s skin, with one’s place in the world—is something so many take for granted, a state of being that a person eases into after years of having the particulars of their identity reinforced by media and popular culture.

What effect, for example, would a more diverse portrayal of beauty have had on a young Coral Johnson? As a teenager in a predominantly white area of East Texas, Johnson, the child of a Black father and a Hispanic mother, was an anomaly. The Bible Belt town wasn’t so welcoming to someone who wore crop tops and sported tattoos. Labeled a slut and a bad influence, Johnson ultimately became one, landing in and out of juvenile detention centers. “I was different and I couldn’t really find my group, so I found it in trouble and drugs and stuff that teenagers should not be getting into,” says Johnson, a non-binary, gender non-conforming lesbian.

At around that time, Johnson, like Cruz, developed vitiligo—just another “sprinkle of uniqueness,” as they refer to it. Before leaving Texas for good, Johnson worked for some time at a gas station and the large patches of lighter skin drew attention. Not the good kind. “People would make all sort of weird comments like ‘Did you get burned?’ or ‘Did you forget to put makeup on the other side of your face?’” Johnson recalls. “Nobody really knew about vitiligo yet. It wasn’t really a thing that was seen in beauty ads.”

That’s slowly changing, of course, most notably thanks to Winnie Harlow, a model with vitiligo who’s appeared on the covers of several international fashion magazines and in advertisements for brands like Desigual and Puma. Now, with Prim-n-Poppin, it’s Johnson’s turn: Their face has replaced the detached visage of the woman that so struck Drury from that old lipstick ad. The implications of the swap aren’t lost on Johnson: “Images like this not only would have changed my thinking [as a teenager], but everybody else would have seen them too and maybe not treated me so awfully or made me feel like such a wrong type of person. It would have changed a lot for everybody.”

Ava Trilling agrees—she’s the other half of the photograph with Johnson in it. And unlike the man in the original, her touch is far less menacing, almost reverential. Not quite the kind of pictures Trilling was used to seeing when she’d scroll through her Instagram feed at age 17. No, those photos were of models like Bella Hadid—impossibly thin, with smooth skin and an effortless air of faultlessness.

Suddenly, the self-described tomboy, who’d never given her weight a second thought, became hyperaware of how her clothes fit. As the lead singer of a rock band called Forth Wanderer, Trilling began to wonder if there was a particular persona she needed to embody. They’d achieved a certain degree of notoriety back then, touring the world and signing a deal with Sub Pop Records, the original label of Nirvana. “I had become obsessed with my image,” says Trilling, who now identifies as queer and has a girlfriend.

Trilling’s obsession led to an eating disorder. At first, she was just trying to be healthier, avoiding too many bagels and burgers. You know, the “bad” stuff. But soon, her eating became compulsively restrictive—and she was rewarded for it. Her weight started to drop, she started to feel sexier, and the whole vicious cycle began. At one point, she was 5’ 9” and 114 pounds—10 pounds less than what’s considered a healthy weight for a woman of her height, according to the CDC.

Eventually, her family intervened, therapy began, and Trilling was diagnosed with anorexia. But because she says she didn’t always appear unhealthy, help came just in the nick of time. It’s this close-call scenario that deeply concerns Cruz: “There are so many people struggling—literally killing themselves—who are turned away from those who could help because they don’t fit the mold of what a person with an eating disorder is supposed to look like,” Cruz adds. Yet it’s a problem that significantly impacts the queer community: According to the National Eating Disorders Association, teens who identify as LGBTQ+ may be at a higher risk of disordered eating than their heterosexual peers. Cruz feels strongly that these people—especially if they’re also BIPOC—are often left out of the conversation.

Because of her anorexia, Trilling nearly had to drop out of high school so she could receive inpatient treatment. Thankfully, she didn’t, but the pace at which she became swept up by the disorder continues to alarm her. Were those Instagram images, taunting her with unachievable perfection, to blame? Partly, Trilling, now 23, believes. Research suggests a connection, too, with Instagram use linked to increased symptoms of certain eating disorders, according to an online survey of 713 participants.

And Trilling worries that it’s only gotten worse for teens since she was an adolescent, innocently scrolling on her phone. “During a pandemic, these girls are looking at models and influencers promoting diet pills and waist trainers—it’s really f*cked up,” she says. “I mean, I can’t even begin to think where I might be now if I were a young person looking at these things.”

That’s not to say social media is all bad. Many are now choosing to use their platforms to promote acceptance and self-love. Kaguya is one of them. She didn’t love herself very much as a young girl growing up in Florida though. The child of immigrant parents, she never quite felt like she was enough—thin enough, Asian enough, American enough. At home, she was hardly the model of a perfect Korean daughter. Her size and penchant for drawing and singing drew the ire of her mother. At school, her struggle to grasp English (she didn’t really master the language until age 12, she says) only added to her growing sense of otherness. “I was bullied,” Kaguya says. “I constantly felt like I stuck out like a sore thumb.”

Before long, ideas of assimilation crept in. Maybe losing weight would help? So from the ages of eight to twelve, Kaguya estimates she tried ten to fifteen different diets. One involved downing a Gatorade in the morning, starving herself until dinner, chugging a liter of laxative Ballerina Tea afterward, and doing Dance Dance Revolution for two hours. This particular madness was brought on by an especially humiliating incident in high school when a food fight broke out in the hallway and a classmate asked Kaguya to stand in front of him and his girlfriend to block the refuse from pelting them. Is that what my body is, Kaguya thought, a human shield?

Eventually, the now 31-year-old found her way to New York City, graduating with a degree in photography from the School of Visual Arts in 2015. The next year was a turning point: After leaving an abusive relationship, Kaguya came out of several months of depression with a newfound sense of self-worth. “I guess in a sense I finally realized and came to terms with the fact that I didn’t need anyone’s acceptance in order to be myself and be vocal about what I deserved,” she says.

That Halloween, the photographer, who never felt comfortable being in front of the camera herself, snapped a selfie. And it was as if something long-hibernating had awakened inside her. The idea that she could express herself in any way she pleased—free from the judgements of parents, schoolmates, boyfriends—came sharply into focus. Kaguya stumbled upon the body positivity movement that was starting to permeate Instagram and realized there was something missing from it—her. “I didn’t see any plus-size Asians, so I decided to put myself on there,” she says.

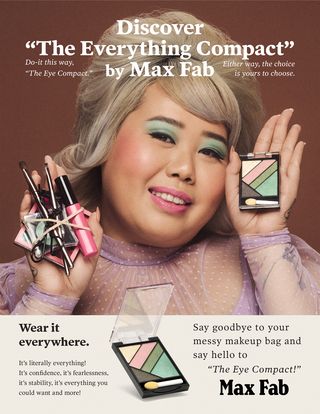

Fifty-eight thousand Instagram followers, endless fashion and beauty shoots, and a contract with We Speak Model Management later, Kaguya found herself in that Williamsburg photo studio, hair teased into a beehive, holding an eyeshadow compact in one hand and six other beauty products, fastened together with rubber bands and resembling a makeshift Swiss Army knife of cosmetics, in the other. Her presence on set was, naturally, to reinforce the bigger themes of diversity and inclusion that are core to the Prim-n-Poppin project overall.

But this particular image—all of them, really—is also about poking some good-natured fun at the oftentimes hilariously unrealistic marketing promises brands made way back when. Kaguya’s vignette takes its cues from an ad featuring a model in full makeup—jet black mascara, powder blue eyeshadow, bee stung berry lips—holding a single compact, as if to suggest that one tiny click-case holds everything a woman could need to recreate the look. “It’s hilarious,” says Drury. “There’s so much more to it than that.”

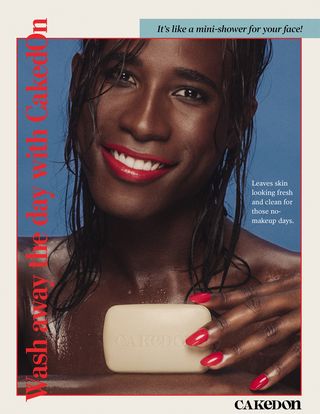

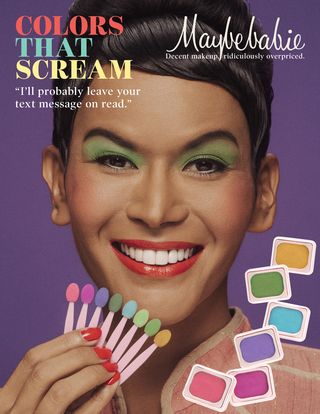

Just as there’s so much more to Prim-n-Poppin than simply uniting the right subject, the right pose, and the right lighting in freeze frame. Once the work of creating the main images was done, Comita and Drury collaborated with art director Stephanie Francis, copywriter Bre Harrison, and prop stylist Sarah Barton Bernstein to transform the photographs into fully realized replicas of period advertisements. The team scoured eBay to find authentic vintage makeup to shoot and overlay on top of the model photos, experimented with different fonts to conjure an authentically retro vibe, and brainstormed tongue-in-cheek names to reference the brands from the originals (Sammy Hansen, Max Fab, Maybebabie). The results are charmingly earnest.

Like the snap of 26-year-old non-binary model Cory Walker holding a bar of soap with the word Cakedon seemingly carved into the front (it was actually done in post-production). The finished product, a play on similar advertisements for makeup removing products that inexplicably feature subjects in full makeup, is arresting: The colorless block offset by Walker’s rich chocolate brown skin—ebony and, quite literally, Ivory.

Before moving to New York from Florida, the Georgia native had become used to caking things on. Instead of makeup, Walker hid behind a disguise meant to mimic the hyper-masculine trappings of traditional Black Southern boyhood. “I really started to second-guess my mannerisms and my behavior, making sure I didn’t move my hands a certain way,” Walker says. “I knew I had to do that if I wanted to have a safe childhood.”

But blending in was never quite Cory Walker’s style. A penchant for Vogue, Vans, and Hot Topic meant they were nothing like the conservative boys growing up on Fort Stewart, an army base 30 minutes outside of Savannah where Walker’s stepdad was stationed. But dreams of a career in fashion helped Walker endure: “It’s literally what kept me alive. I would just say to myself, ‘Okay, one day you’ll be in New York, you’ll be a model, and you’ll have autonomy over your own life. You’ll find your people.’”

Sure enough, eight years later, in 2015, Johnson boarded a plane bound for the Big Apple. Surprisingly though, the experience of trying to break into the world of professional modeling wasn’t all that different from being a young child on that base: adopting a façade seemed to be a pre-requisite. Walker went from one open call to the next with no luck, and it wasn’t long before an understanding of why set in. “This one agent said, ‘I’m going to tell you something and I think it’s really going to help you,’” Walker recalls. “’You need to be more manly. You need to pretend to be a straight boy from Indiana because you’ll never have a career if you present the way you are.’”

Something funny happened in that moment. Rather than despair, Walker felt optimistic. Energized. If there isn’t a space for me, they thought, I’ll just have to make my own space. Good old fashioned networking led to photo shoots, fashion shows, and, two years after the incident with that agent, a relationship with New Pandemics, a casting and management agency dedicated to increasing LGBTQ+ visibility in the industry.

It also led to Walker to the Prim-n-Poppin shoot, where another model, 25-year-old Maria Rivera, is struggling to get her smile just right in front of the camera. Maria is a big-smile kind of girl—joy just seems to emanate from her. But Comita wants something even more over-the-top. A sincere grin simply won’t work here. After a few tries, Rivera nails it.

Never in a million years did Rivera think she’d be living this life. A life that seems so much like a blissful sliver of the glamorous existence led by the four main characters of Sex And The City, the show that let her dare to dream of one day walking the streets of New York.

As a boy in the Philippines, Rivera marveled at the inter-barangay beauty pageants, many of which featured drag queens and transgender contestants. Their transformations fascinated Rivera and stirred something deep inside the heart of the young child, who, as a seven- and eight-year old, would sneak into her mother’s bedroom to put on her strawberry lip gloss. Before she even knew what the term transgender meant, Rivera understood that she preferred her sister’s Barbie dolls to the toy trucks brought home by her father. Quietly nurtured and supported by her mother, even in a deeply Catholic place like Manila, Rivera graduated from high school realizing that she’d been born into the wrong body.

Once she was living as a woman, Rivera was considered passable, a reference to a transgender person who might be mistaken as cisgender. Even so, success as a model—Rivera’s ultimate goal—was elusive. Booking gigs in the Philippines as a transgender woman was tough. Despite some eventual success in her home country, a seemingly sent-from-above visa brought Rivera to the States and, ultimately, to Slay Model Management, the world’s first and only modeling agency dedicated exclusively to transgender talent.

Maria’s struggles are far from unique, says Slay’s founder Cecilio Asuncion. And even when brands and clients are open to featuring trans models, there’s usually a steep learning curve for bookers and casting directors. One of Asuncion’s models, who was competing for the same job with two cisgender men in wigs, was once asked on a casting to take her top off, look “disappointed,” put her shirt back on, and apply lipstick. “I told the casting director that my model was not going to do that. Those are her breasts. She can’t just take her top off,” Asuncion says. “Trans people are not drag queens.”

In the end, Asuncion is the one who brought Rivera to Comita and Drury. Both were immediately interested—just look at that bone structure—and confident that with the rest of their group, they were able to infuse the project with as much diversity as they could in just five shots.

But Prim-n-Poppin won’t end here. Comita has applied for several grants to help keep this self-funded project going. The goal is to put even more diverse talent—different ages, a broader range of races and ethnicities, models with varying physical abilities—in front of the camera. In a sense, they’re rewriting the history of mainstream beauty to include all the people who were edited out the first time. “When you think of the generations of young kids who could be looking at advertising right now and see a more inclusive space, you think, ‘Of course that’s what we should be doing,’” Comita says.

***

Photographer/Creative Director: Julia Comita @juliacomita

Makeup/Creative Director: Brenna Drury @brennadmakeup, using Tarte Cosmetics and Danessa Myricks

Talent:

Maria Rivera @immariarivera

Kaguya @p.s.kaguya

Cory Walker @corywalkers

Jesi Taylor Cruz @moontwerk

Ava Trilling @avatrillz

Coral Johnson-McDaniel @sadistitt

Makeup Assistant: Sean Kosugi @shokuma_

Hair: Raina D. Leon @rainaleonhair

Stylist: Joiee Thorpe @joieestyled

Art Department: Sarah Barton Bernstein @propstylist

Art Director: Stephanie Francis @stephiejae

Lighting: Daniel Johnson @thatdanielcamera

Copywriter: Bre Harrison @bresayshella

Retouching: Super Utopia @superutopia

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

More Stories

5 Tips For Launching a Blog to Highlight a Brand

Promotions – a holiday gift for shopper and retailer

10 Makeup Items I Reach For Everyday & Would Never Be Without – The Anna Edit